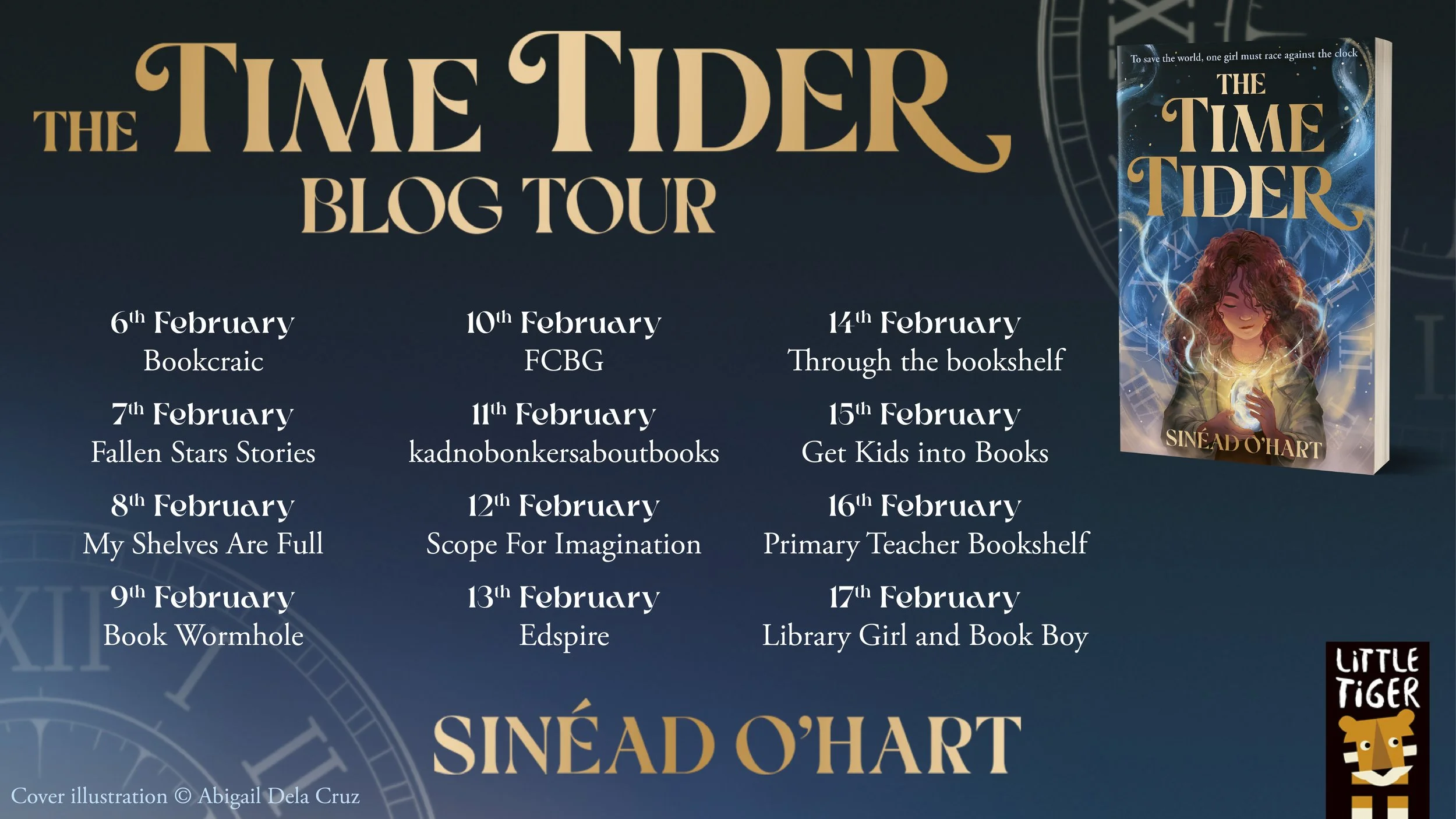

Blog Tour: The Time Tider

I am beyond delighted to be taking part in the Blog Tour for ‘The Time Tider’ by Sinead O’Hart. I have loved each of Sinead’s books so far for very different reasons, but this latest one really is something special. It offers mystery, adventure and peril whilst challenging the reader to wonder what they would do if they were in Mara’s shoes. Completely compelling, it is an irresistible story- one to return to again and again!

For this stop on the Blog Tour, Sinead shares this fascinating piece about the History of Clocks and Timekeeping.

One of the most enjoyable parts about being an author is the research you sometimes get to do when you’re writing a book. Some books require more background work than others – some require none at all! – and others require loads. My new book, The Time Tider, was somewhere in the middle. It’s a book that’s sort-of about time travel, but which is more about asking questions around the morality of power and who gets to be in charge, and what to do when the people in charge get corrupted and start misusing the power and responsibility that was placed on their shoulders. It’s a book about loss and grief, too, and the importance of making the most of every second we have with our loved ones. And, of course, it’s a cracking adventure with lots of thrills and twists, and two of my favourite characters, Mara and Jan, a girl who lives on the road and a boy with secrets of his own, who have to work together to save not only themselves, but the fabric of Time itself.

In order to write The Time Tider I did some research into how human beings have thought about time for as long as we have historical records, and I learned about clocks and timekeeping and how time – and how it’s measured – can tell us loads about society and culture and structures of power. Of course, when you’re dealing with time as a concept in a book, you run afoul of pesky things like physics and relativity and time dilation and quarks and gravity and black holes… and sometimes, you can become bogged down in the fact that people much cleverer than yourself have spent entire careers trying to understand the way time works – and they still don’t have all the answers. I also read about the physics behind time (turning my brain into a pretzel in the process), but I was more interested in the history of how we’ve measured time – and mostly, what I learned was that time is a very complicated business, and I honestly have no clue how any of it keeps ticking along.

The first means of measuring time, in all likelihood, involved using shadows – because, of course, an object’s shadow changes position during the course of the day, as the sun moves through the sky. People have long noticed this, and used it as far back as the 3rd century BCE (Before the Christian Era – so, over two thousand years ago) to calculate the circumference of the Earth. This was done by a brilliant Greek mathematician named Eratosthenes. He used two gnomons (which are tall objects designed to cast a shadow, and can be used to tell the time as part of a sundial or shadow clock) placed in two different cities, and measured the difference in the angle of the shadows cast by the gnomons at midday. From that, and using the distance between the cities, he was able to work out not only how big the Earth is, but also its axial tilt (the angle of the Earth). At around the same time, during the First Punic War, the Romans took a sundial from Sicily and put it on display in Rome as the first public clock. The playwright Plautus complained about how the human body used to be the best clock – by which he meant he could tell when it was lunchtime by the grumbling of his tummy – and now people were using technology to tell time instead! This complaint has been made at several points in history (and it’s one of the inspirations behind The Time Tider itself).

In Athens, in Greece, there’s an amazing place called the Tower of the Winds, which might date from around the 2nd century BCE. It has shadow clocks (sundials), a wind vane, and a water clock – so it’s like the world’s first meteorological station. Water clocks were a way to measure time through the precise dripping of water through a carefully bored hole in one vessel, which fell into a second, lower, vessel marked with the hours. These clocks were made with great skill, so that the water filled at a predictable and accurate rate during the day, and that it took exactly the same length of time to fill each hour. (Well - more or less.) They were known as ‘klepsidras’, which means ‘water stealer’. In medieval China, we see candle clocks beginning to appear – these were candles which burned at a steady rate, reducing their height each hour so that a person could tell by looking at it what time it was. These sorts of clocks became widespread and were used in Anglo-Saxon England by King Alfred the Great, as well as by the great Mesopotamian inventor Ismail Al-Jazari (d.1206), who made a clock that played music every hour! In later medieval China there were fire clocks which worked by burning a stick of incense, and as the hours passed the burning stick would drop metal balls into a shallow plate placed beneath the clock. The clattering of the balls would alert people to the passing of the hours. Some of these clocks worked using fragrance, so that each hour had its own particular scent; as the incense burned, and the scent changed, the user would know that time had passed. Hourglasses – where sand flows at a known rate through a glass vessel, which is housed inside a wooden frame – were also widely used, but nobody is really sure where they were first invented. Certainly, they’ve been around since at least the eleventh century – a thousand years ago.

From the medieval period, about the thirteenth century, mechanical clocks begin to be invented. Bell towers (which were already ringing out the hours through someone ringing a physical bell) began to be mechanized, and the earliest clock tower with a face and hands comes from the 1380s, in Venice. There was one in Salisbury, in England, from around the same time. And here’s where our friend Plautus would have had a lot to complain about: it’s from this time that people begin to think about time in a different way to before, where time becomes something imposed upon people, and clocks begin to force a sort of order or structure on people’s days and lives, disrupting their personal time. The widespread appearance of public clock towers made people feel they had to be eating lunch when the clock struck one (rather than when they were hungry) and that they had to be at church when the clock struck ten, or that they had to be asleep when the clock struck eight. The phrase ‘time is money’ dates from around 1719, when ideas about time and productivity and work start to get intertwined – time was no longer something personal and private, but now your time belonged to your employer. It was also something precious, given by God, something you could waste (which was sinful), and in the late seventeenth century a writer named Richard Baxter wrote about wasting time as being the same thing as robbing from God himself.

In the nineteenth century, we begin to see time and time-zones becoming established and regularized, and one of the main reasons for this was so that accurate train timetables could be drawn up. Prior to this, each town and village would have had its own time! So, GMT (Greenwich Mean Time, which we still use today, and which regularizes what time it is in Britain, Ireland, and lots of other countries) became the primary way in which we map time-zones around the world. Nowadays, we use quartz watches (quartz vibrates at a set rate, and can be successfully used to calibrate clocks) or atomic clocks (which work similarly – using atoms which vibrate at a set rate to power the most accurate clocks humanity has yet invented) to measure time on land, on sea, and even in space – but sometimes I wonder, even now, do we really understand how time works? Maybe we never will!

Many thanks to Sinead for joining me on the Bookshelf today and sharing this piece. I cannot recommend ‘The Time Tider’ highly enough and know that it is a book which teachers will enjoy introducing their children to- it would work brilliantly as a Guided Reading text! Thanks to Little Tiger for inviting me to be part of this tour- and make sure you check out some of the previous posts as well as the three remaining days ahead.

The Time Tider Sinead O’Hart

Little Tiger ISBN: 978-1788953306

You can read my review of ‘The Eye of the North’ here.